May 20, 2021 —

“I never thought about being the first of anything. All I wanted to do was be a pilot and fly.”

Mara Huling Langevin was born in Hollywood, California, and was the youngest of five children. Her mother was a kindergarten teacher for over 30 years and her father had several different jobs (U.S. Navy – Korean War Veteran, law enforcement, aerospace industry, and education). Her mother expected all of the Huling kids to have a college education paid for by a full scholarship.

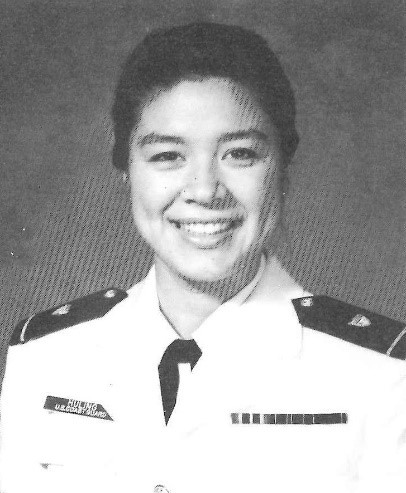

Mara applied to all the U.S. military service academies and chose the U.S. Coast Guard Academy (CGA) because of the Academy’s mission. During her academy years, Langevin remained on the Commandant of Cadets’ list all four years, was the captain of the Lady Bears volleyball team and won All New England in the Pentathlon for indoor track and field.

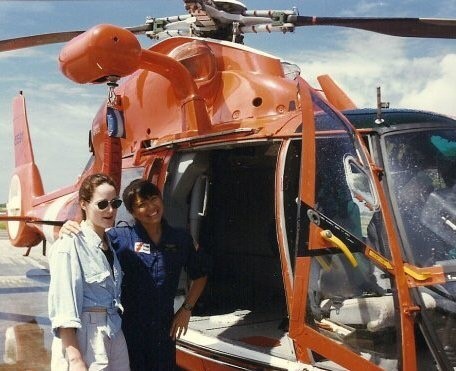

Huling graduated the Academy in 1991 and spent her first tour as a deck watch officer on Coast Guard Cutter Resolute. In 1993, she was selected for flight school and earned her wings of gold on April 21, 1995. Her first aviation assignment was Coast Guard Air Station Barbers Point, Hawaii, where she flew search and rescue missions in the HH-65A Dolphin helicopter. She then qualified as an instructor pilot and taught at the Coast Guard’s Aviation Training Center in Mobile, Alabama.

Langevin has the distinctions of being the first Asian-American female aviator and first minority female aviator in the history of the U.S. Coast Guard.

Her achievement followed other Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) firsts including:

- 1853 – The first documented case of an Asian man serving on board a Coast Guard cutter.

- 1942 – Lt. Cmdr. Carmelo Lopez Manzano, Ensign Conrado Aguado, and Lt. j.g. Juan B. Lacson, former officers of the Philippine military, became naturalized U.S. citizens and became the first officers of Asian ancestry to serve in the Coast Guard.

- 1945 – Grace Chin enlisted in the Coast Guard Women’s Reserve (SPARs), and became the first Asian-American woman to wear the Coast Guard uniform.

- 1949 – Jack Ngum Jones became the first minority cadet to graduate from the Coast Guard Academy and the first Asian-American officer in the Coast Guard.

- 1958 – Manuel Tubella, Jr. became the first Asian-American and second minority Coast Guardsman to become an aviator in the Coast Guard.

- 1980 – Moynee T. Smith became the first minority and Asian-American female to graduate the Coast Guard Academy and the first known Asian-American female commissioned officer in the Coast Guard.

And many others… (as noted in the U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Office Asian Americans & the U.S. Coast Guard Historical Chronology document ).

).

Her achievement blazed the trail for future AAPI aviator firsts including:

- 2008 – Susan E. Walters earned her wings, becoming the second Asian-American woman to do so for the Coast Guard, and the first to fly fixed wing aircraft.

- 2012 – Adriana Knies Gaenzle earned her wings, becoming the third Asian-American woman to do so for the USCG and the first to fly the MH-60 Jayhawk helicopter.

In the Coast Guard, we call this the Long Blue Line. The Long Blue Line is a term we use to refer to the history of Coastguardsmen and women whose stories contributed to what the Coast Guard is today. Reflecting on the Long Blue Line is a way we honor those who came before us and paved the way.

I had the opportunity to chat with Mara about her time in the Coast Guard and life after the Coast Guard. I hope that sharing her story may inspire future generations of AAPI by seeing themselves in her story, to be inspired to make their own stories, join the long blue line, and chase their own dreams.

What inspired you to join the Coast Guard?

knew that the only way I could afford to go to college was to get a scholarship, and the only way I could afford to learn to fly was through the military. Those two factors steered me to look into the service academies. When choosing which academy, I chose the USCGA because of the mission. Saving lives seemed to fit my personality much more than taking them. I also had the fortune to visit USCG Air Station Los Angeles and was impressed by how approachable and friendly the pilots were. They were nothing like the stereotypical pilots I watched in the movie Top Gun as a teenager.

Did you know you were a “first” w hen you started flight school? If so, how did it affect you If not, when did you find out?

hen you started flight school? If so, how did it affect you If not, when did you find out?

I didn’t know that I was the first AAPI or minority woman Coast Guard flight student until about 2011, 10 years ago maybe, and by that time I was out of the Coast Guard. So, being the first really had no effect on me because I didn’t know, but being a minority always affected me. There was always self-imposed, extra pressure to prove myself. I wanted to show I was just as capable and motivated as any of the other flight students.

What was interesting was that about halfway through the flight school program, there was a female African American Coast Guard member flight student who checked in well after I was halfway through the program. I remember hearing about her and that her attendance was a big deal because she would’ve been the first African American female U.S. Coast Guard aviator. Unfortunately, she didn’t complete the training. I can’t imagine the extra pressure she must have felt. Because my completion of flight school didn’t bring any special recognition by the USCG, I really didn’t think much of it. I was just happy I earned my wings, survived flight training, and made my dad proud.

Now that you know you were a first, do you consider yourself a trailblazer? What does it mean to you to be a first?

I really don’t consider myself a trailblazer. Perhaps because I didn’t observe that I had to overcome more obstacles than any other Coastie (male or female) to get where I was. I went to flight school with the first female U.S. Marine Corps pilot, Sarah Deal. She and I became good friends during flight school and during training she received a lot of harassment from some of the Marine Corps male flight instructors. At that time there was definitely apprehension from some in the Corps to allow women into the all-male aviation community. She was a trailblazer in my eyes because with every one of her flights she felt like she had to have a perfect “hop” (flight) in order to dissuade any negative feedback for women aviators in the Marines. I didn’t feel that pressure and know that Janna Lambine (first female USCG aviator) probably went through a lot more than I did.

Now that I know I’m the first, I do feel a sense of pride and responsibility to represent others who have similar backgrounds and look like me. I know the importance of seeing people who look like you with similar backgrounds in positions that you aspire to; it’s an important motivator. If I motivate others to achieve their dreams, that makes me very proud.

Did you have mentors at the Academy or at flight school? Who were they and what did they provide for you?

I had a really good friend at the Academy, who also went to flight school and then on to teach at Aviation Training Center (ATC) Mobile, who I would consider a mentor. Polly Pieterek Bartz (class of ‘90) was only a year ahead of me at the Academy but she always seemed to have wisdom beyond her years and gave great advice. She was the kind of friend who you could confess your insecurities to and she would boost you up and make you feel better. She was also an excellent instructor pilot and easily earned the respect of all her peers, flight crew and students, male and female, while we were both stationed at ATC Mobile. She helped me decide to go to ATC Mobile and answered questions on how to handle students, teach certain flight maneuvers, and how to run simulator flights. Her mentorship/friendship helped me become a better pilot and person. My advice: It’s important that your mentor allows you to ask questions without judgement. As a woman, I often thought asking questions would show lack of knowledge to the other male pilots and I would be judged. Asking questions to a women mentor and friend like Polly, freed me of that worry.

What challenges (if any) did you face as a minority female?

I didn’t feel like there was specific racism against me while I was an officer in the Coast Guard. There were, at times, derogatory comments made about Asians and minorities in general that weren’t directed at me but did make me feel uncomfortable. When I spoke up against those comments, I received smirks and eyerolls. I think there were also perceptions that because I was quiet, more introverted, and a bit self-deprecating that I wasn’t confident in my ability. I was always taught to have humility as part of my culture. In the U.S. military, the opposite is the norm. In the military I’ve heard people say, “always have something to say and if you don’t know something, sound like you do or make it up.” That definitely wasn’t my personality but that didn’t mean I wasn’t confident in my ability to complete tasks given to me.

Do you think the challenges minority females face today are different than when you were in flight school?

I’d like to think that the challenges are less today with more minority women attending flight school. I think there is strength in numbers and being able to lean on each other and pick each other up is important for your state of mind. I was fortunate to have friends that didn’t care that I didn’t look like them. I made a couple of good friends in flight school that I leaned on for emotional support, and I met my husband in flight school who was my number one fan. He was the best thing that happened to me at flight school.

What’s the story of your first rescue?

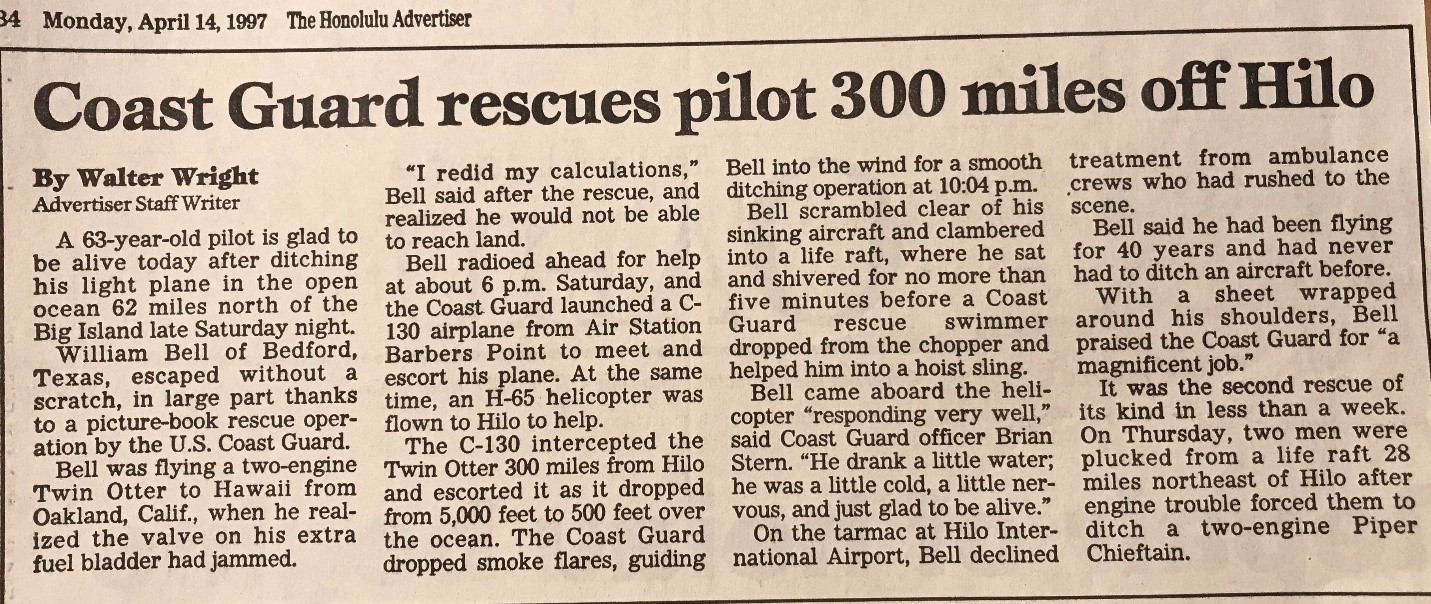

My first rescue in the right seat (meaning I was at the controls during the rescue) was a ditched civilian Twin Otter aircraft off the east coast of the Big Island, Hawaii. I was with Ron Agnich, who was the aircraft commander and an experienced flight mechanic, and a rescue swimmer. The Twin Otter was a dual prop engine, fixed wing, civilian aircraft. This particular plane suffered a malfunction with the fuel transfer switch while in transit from California to Hawaii. The pilot realized he didn’t have enough fuel to make it to the Big Island so he called the Coast Guard and communicated his plan to ditch in the ocean.

It took us two sorties (Oahu to Hawaii for fuel, then out to sea) to get to the location where the plane went down. By the time he had to ditch, it was night and the sky was black with no illumination and no horizon. A C130 from Barbers Point circled above the plane talking to the pilot on the radio, going over procedures and keeping the pilot calm. When time came for him to make the ditching, the C130 dropped a line of flares into the water in the direction of the wind, to give the pilot a visual reference. We were actually on scene as the pilot made his controlled ditching and we picked him up within five minutes of being in the water.

It was eerie to watch the Twin Otter’s anti-collision lights approach the flares in the water and extinguish in the blackness with no further radio transmissions from the pilot. I then flew the HH-65A into a descent, leveling off at 25’ into a controlled hover. We deployed the rescue swimmer and then the basket. We picked up the pilot in the basket (who had been floating in his life raft), recovered the rescue swimmer and headed back to the airport in Hilo, Hawaii. It was a smooth rescue, and the pilot had barely a scratch on him.

The funny part of the whole evening was after we shut down the helicopter and waited for the ambulance. I approached the rescued pilot, took off my helmet and told him I was happy he was okay. I then commented that he did an excellent job ditching the plane. He looked at me and asked where the pilots were because he wanted to thank them. When I told him I was the pilot, he looked a little confused. He said, “Thank you,” and walked away. I don’t think he believed me and when he saw Ron a little bit later, he thanked him and shook his hand.

(Article for reference below. There are a few mistakes in the reporting but for the most part it’s accurate.)

Is it important to have diverse air crews? Why or why not?

In my opinion, it is absolutely important to have diverse crews. First, The people we serve are diverse so to fully understand their needs, we have to have similar representation in our air crews. Second, If I recall, in Coast Guard Aviation there was a concept called CRM or Crew Risk Management. It used to be termed Cockpit Risk Management and then the Coast Guard realized that the entire crew has critical input to offer when evaluating the risk, not just the cockpit so they changed the “C” to “crew.” Part of CRM is soliciting input from the entire aircrew when evaluating risk and making decisions. The flight mechanic, rescue swimmer, and pilots all come from varied backgrounds and have different roles and responsibilities. To see the entire risk to mission, you must get the point of view from the whole team. Everyone has a different lens (experience, culture, gender, ethnicity, etc.) that we see through and we view problems differently. By tapping into this diversity we can find unique solutions. We must invite differing opinions from diverse backgrounds, especially in navigating today’s diverse and complicated world.

How do you celebrate your culture?

I remember going to Bon Dance Festivals when I was a young girl with my mother in Southern California. We would dress up in our kimonos and spend the night dancing in a large circle, listening to the singing/music and eating Japanese food. Although my kids have no interest in Bon Dance, we love eating Japanese food, especially ramen and sushi. The family went to Japan several years ago and I was able to show them more about my mother’s culture and Japanese history. We were supposed to go to the Olympics last summer and see Kyoto but due to the pandemic it was cancelled. Next year, maybe we’ll just go to Kyoto. I also make gyoza with my daughter as a fun cultural activity together. I also love Taiko! I took Taiko drumming lessons a couple of years ago and absolutely loved it. With my work schedule, I don’t have a lot of time to put into it but it’s on my retirement list to be a real Taiko master. Living in Hawaii, I’m lucky there is a large Japanese American population so there are always Japanese festivals, like the Shinnyo Lantern festival. Unfortunately, due to COVID the past year most of the festivals were canceled. I am also part Cherokee Native on my father’s side and he took me to a Pow Wow once when I was in high school. I enjoyed that experience and realized how similar it was to the Bon Dance festival. People singing, drums playing and a large circle of men and women dancing in step to singing and drum beats. I’ve attended a few Pow Wow’s after moving to Hawaii as well.

How are you processing recent news of increased attacks and hate crime against the AAPI community?

How are you processing recent news of increased attacks and hate crime against the AAPI community?

It saddens me and scares me. I worry about my siblings. My sister lives in Northwest Oregon where there aren’t many AAPI and I was stationed there my first tour out of the Academy. I worry that she will be a victim of violence because I experienced racist comments when I was there. There are always places that I know I might get chastised for looking different but I seldom feared for my safety, until now. Racism against non-whites is a problem in this country and until we ALL admit it exists, we won’t be able to solve it. It’s not just Caucasians against African Americans, it’s African Americans against Asian Americans, Asian Americans against Hispanic Americans, etc. We ALL need to do some self-assessment and ask ourselves how we have contributed and how we can do better to stop racism.

Is there anything you’d like to say to the current or future AAPI servicemembers who are shaping the Long Blue Line today?

Be proud of the work you are doing in the Coast Guard. It’s an honorable profession, great organization, and is well respected. This is a testament to the people who make up the organization. AAPI, be yourself, and don’t feel like you have to act or carry yourself like others around you to fit in. If you have different cultural practices, explain them to others who don’t understand, teach them (some people may fear or criticize what they don’t understand). There will always be people who won’t like you regardless of what you do, or how well you do your job, or how hard you work. Ignore them, they aren’t worth investing your precious time and energy in. Your background and diversity make this amazing organization stronger and more efficient.

Today, Langevin is a Humanitarian Assistance Advisor to the Military with The U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID), Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (BHA). USAID/BHA is the Lead Federal Coordinator for any U.S. Government assistance to foreign countries suffering from the effects of natural disasters or complex emergencies. Her most recent response was supporting the Internally Displaced People (IDP) in Iraq in 2019. She is currently an advisor to the INDOPACOM Geographic Combatant Command, coordinating Department of Defense support to disasters in the Asia-Pacific. Langevin is a wife, and a mother of two. She continues to support and mentor AAPI cadets at the Coast Guard Academy and officers in the fleet.

For further reading about the Long Blue Line of AAPI Coast Guard History visit: