Dec. 11, 2020 —

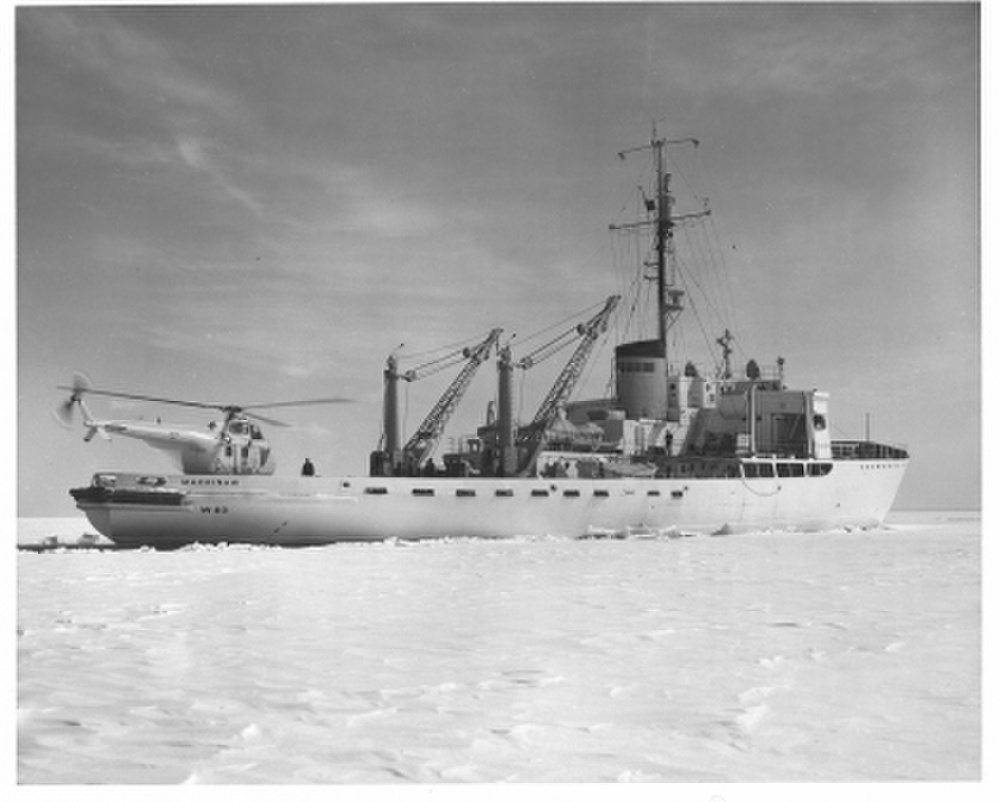

Normally, lake ice begins thawing at the end of April, but “Big Mac”--as the icebreaker is affectionately called in the Lakes region--has opened shipping lanes as early as the third week in March, thus facilitating the early movement of millions of tons of iron ore, grain, and other vital cargo.

U.S. Coast Guard Public Affairs

For generations, Great Lakes shipping ceased in the frozen winter months only to return with the spring thaw. During World War II, the “Arsenal of Democracy” had to keep American factories running year-round. This was especially true of steel-making plants along the Great Lakes, and those plants needed iron ore, which meant keeping the shipping lanes on the Lakes open as long as possible. The only way to do so was to build a Great Lakes icebreaker. Congress authorized the funds to construct that icebreaker on Dec. 17, 1941, just 10 days after Pearl Harbor.

Design of the Great Lakes icebreaker Mackinaw (WAGB-83) was based on the Coast Guard’s “Wind”-Class icebreakers designed to serve in Arctic waters. Mackinaw’s plans  were developed by the acclaimed naval architecture firm of Gibbs & Cox from designs drawn up by the Coast Guard’s Naval Engineering Division. The Coast Guard’s designs were based on research conducted by Coast Guard engineer, Lt. Cmdr. Edward Thiele, during a trip to Europe to study Scandinavian icebreaker design and the new Soviet icebreaker Krassin.

were developed by the acclaimed naval architecture firm of Gibbs & Cox from designs drawn up by the Coast Guard’s Naval Engineering Division. The Coast Guard’s designs were based on research conducted by Coast Guard engineer, Lt. Cmdr. Edward Thiele, during a trip to Europe to study Scandinavian icebreaker design and the new Soviet icebreaker Krassin.

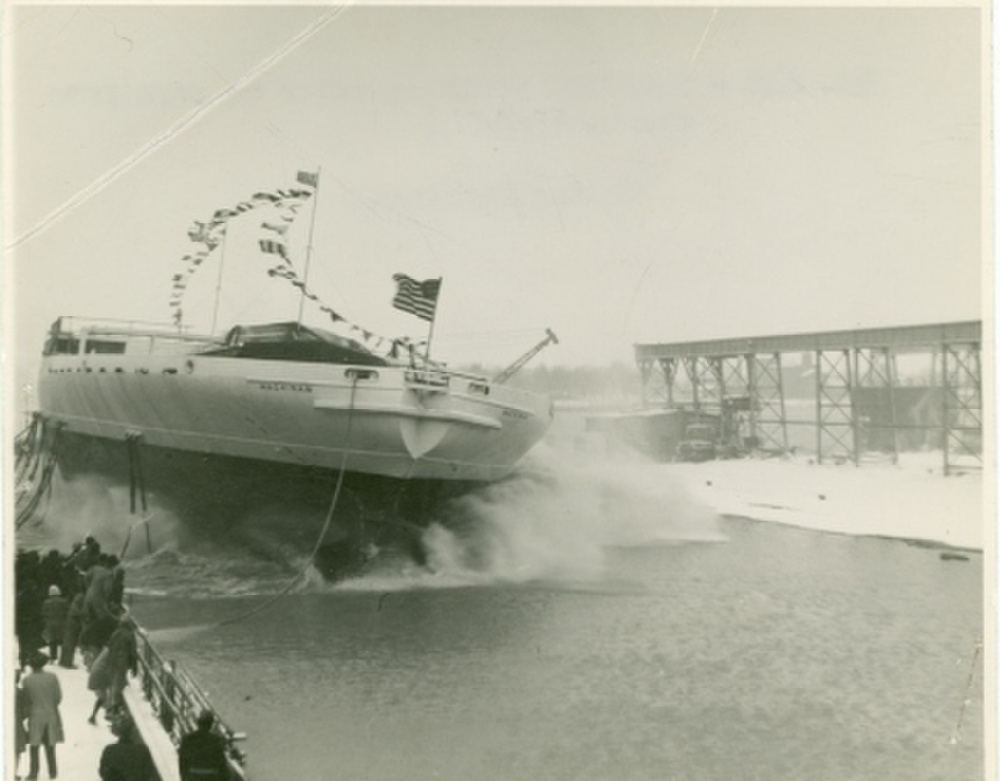

Mackinaw’s keel was laid March 20, 1943, at the Toledo Shipbuilding Company in Ohio. The cutter was launched and christened Mackinaw a year later, on March 4, 1944. It was supposed to be named Manitowoc, but the Navy had already assigned that name to a patrol frigate. Mackinaw was commissioned Dec. 20, 1944, and its first commanding officer was Cmdr. Edwin Roland, later Commandant of the Coast Guard. Local newspapers heralded the icebreaker’s arrival on the Lakes, claiming that “. . . with the assistance of the powerful new icebreaker. . .the Coast Guard hopes to keep Great Lakes shipping lanes open one month longer each year, and to enable newly-built naval and cargo craft to move from Great Lakes shipyards to the ocean during the winter months, averting lo ng delays.”

ng delays.”

Mackinaw’s breadth and length were greater than the “Wind”-Class icebreakers. According to Thiele, “Mackinaw was nothing but a “Wind”-Class ship that was squashed down and pushed out and extended to meet the requirements of the [Great] Lakes.” Mackinaw was designed wider to cut ice channels for elongated Great Lakes bulk carriers, but that width prevented it from transiting the Welland Canal and leaving the Great Lakes. The icebreaker’s powerplant included six 2,000 horsepower opposed piston diesels generating electricity to drive its two stern screws and one under its bow to grind up ice. Mackinaw also had trimming pumps for its special heeling tanks.

The Mackinaw could break two and a half feet of ice continuously and up to 11 feet by backing and ramming. Its hull strength derived from its design and construction. The icebreaker’s draft was considerably less than its “Wind”-Class sisters with a hull built of one and five eighths inch mild steel insulated with cork. Like the Coast Guard’s “Wind”-Class icebreakers, Mackinaw’s frames were spaced about 16 inches apart resembling a truss similar to an inverted hangar with an inner  shell built inside the truss. The volume between the inner shell and outer hull plating was divided into tanks used to store fuel and carry water ballast for its heeling pumps. The heeling pump system helped free the cutter when stuck in the ice and was capable of transferring 160 tons of water from one side of the icebreaker to the other in about one-and-a-half minutes.

shell built inside the truss. The volume between the inner shell and outer hull plating was divided into tanks used to store fuel and carry water ballast for its heeling pumps. The heeling pump system helped free the cutter when stuck in the ice and was capable of transferring 160 tons of water from one side of the icebreaker to the other in about one-and-a-half minutes.

After commissioning in January 1944, Mackinaw took up station at Cheboygan, Michigan, and began icebreaking duties Jan. 20. The icebreaker’s effectiveness in keeping the shipping lanes open longer than ever before was pointed out in an information bulletin which stated: “In the years previous to the Mackinaw, general navigation on the Great Lakes was closed to shipping due to ice on the average of about four and a half months a year. The Mackinaw has reduced this closed season to an average of about three months a year.”

Mackinaw’s icebreaking cruises followed the shipping lanes through the Straits of Mackinaw, and from Lake Superior along the St. Mary’s River, down to the lower Great Lakes. The icebreaker carved roomy tracks in Lake Superior’s frozen Whitefish Bay, then it cut wide swaths in the St. Mary’s River so  lake carriers could make turns in river bends without getting stuck. If a freighter did get stuck, Mackinaw would circle the vessel to clear the ice out around it.

lake carriers could make turns in river bends without getting stuck. If a freighter did get stuck, Mackinaw would circle the vessel to clear the ice out around it.

Every year, Mackinaw spent about 70 days breaking ice. The season traditionally began in mid-December and ended in the spring. However, the cutter began breaking ice for about six weeks, until mid-February, then went into a one-month “charlie period” for maintenance and crew rest. This break proved essential for crew rest because Mackinaw broke ice around the clock and noise generated by the hull passing through ice reverberated throughout the ship, even requiring hearing protection at times.

After the war, Mackinaw continued performing seasonal icebreaking duties. The “Spring Break-out,” the opening of the annual shipping season, began as early as March and icebreaking continued as late as May. For example, in mid-May 1947, aided by the icebreaking buoy tender Coast Guard Cutter Tupelo, Mackinaw restored order to frozen Buffalo Harbor, which was ice-blocked, trapping dozens of vessels. The icebreakers freed 38  steamers, escorted them into the harbor and freed and escorted another 49. The following year, in mid-March, Mackinaw repeated these rescue efforts opening a passage that freed 12 ice-blocked ships at Buffalo. Mackinaw performed similar operations nearly every spring for the next 60 years.

steamers, escorted them into the harbor and freed and escorted another 49. The following year, in mid-March, Mackinaw repeated these rescue efforts opening a passage that freed 12 ice-blocked ships at Buffalo. Mackinaw performed similar operations nearly every spring for the next 60 years.

Mackinaw kept busy in later years. For example, in just a 10-year span of the 1960s, it performed numerous humanitarian missions. In April 1960, the cutter assisted the ice-damaged motor vessel Henry Phipps, a 585-foot ore carrier. After welding shut cracks in the ore carrier’s hull, Mackinaw towed the damaged freighter to safety through the ice. In October 1960, the icebreaker freed the grounded motor vessel August Ziesing near Little Rapids Cut at Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. In May 1965, Mackinaw served as on-scene commander following a collision between the motor vessel Cedarville and Norwegian motor vessel Topdalsfjord near Mackinaw City, Michigan, in which the Cedarville later sank. In October 1966, the icebreaker stood by the grounded M/V Halifax 40 miles south of Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. On Nov. 21, 1966, Mackinaw transported 29 crewmen from the grounded German motor vessel Nordmeer to Alpena, Michigan, and, on the 29th, the cutter evacuated the remaining crew. In April 1968, the icebreaker helped free motor vessel W.B. Schiller from heavy ice in Lake Superior. And, in April 1970, Mackinaw helped free the grounded motor vessel Stadacona near the Mackinaw Bridge.

Mackinaw kept busy in later years. For example, in just a 10-year span of the 1960s, it performed numerous humanitarian missions. In April 1960, the cutter assisted the ice-damaged motor vessel Henry Phipps, a 585-foot ore carrier. After welding shut cracks in the ore carrier’s hull, Mackinaw towed the damaged freighter to safety through the ice. In October 1960, the icebreaker freed the grounded motor vessel August Ziesing near Little Rapids Cut at Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. In May 1965, Mackinaw served as on-scene commander following a collision between the motor vessel Cedarville and Norwegian motor vessel Topdalsfjord near Mackinaw City, Michigan, in which the Cedarville later sank. In October 1966, the icebreaker stood by the grounded M/V Halifax 40 miles south of Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. On Nov. 21, 1966, Mackinaw transported 29 crewmen from the grounded German motor vessel Nordmeer to Alpena, Michigan, and, on the 29th, the cutter evacuated the remaining crew. In April 1968, the icebreaker helped free motor vessel W.B. Schiller from heavy ice in Lake Superior. And, in April 1970, Mackinaw helped free the grounded motor vessel Stadacona near the Mackinaw Bridge.

In addition to icebreaking, Mackinaw conducted typical Coast Guard duties during the ice-free months. The cutter spent countless hours assisting vessels in distress, engaging in law enforcement and boarding duties, patrolling sail and power boat regattas, as well as annual training cruises for Coast Guard reservists. With the aid of its two 12-ton cranes, Mackinaw could set the heavie

In addition to icebreaking, Mackinaw conducted typical Coast Guard duties during the ice-free months. The cutter spent countless hours assisting vessels in distress, engaging in law enforcement and boarding duties, patrolling sail and power boat regattas, as well as annual training cruises for Coast Guard reservists. With the aid of its two 12-ton cranes, Mackinaw could set the heavie st buoys on the Lakes, and deliver fuel and supplies to Coast Guard shore stations. In addition, Big Mac re-introduced the “Christmas Tree Ship” tradition in 2000. Begun over 100 years earlier when vessels would deliver cargoes of Christmas trees from Upper Lake Michigan to cities like Chicago.

st buoys on the Lakes, and deliver fuel and supplies to Coast Guard shore stations. In addition, Big Mac re-introduced the “Christmas Tree Ship” tradition in 2000. Begun over 100 years earlier when vessels would deliver cargoes of Christmas trees from Upper Lake Michigan to cities like Chicago.

Mackinaw was decommissioned on June 10, 2006, in Cheboygan on the same day that its replacement icebreaker Mackinaw II (WLBB-30) was commissioned. During World War II, “Big Mac” never fought the enemy, but it battled the ice and contributed greatly to winning the war. Later, it wrote many chapters in Great Lakes maritime history. Mackinaw and the men and women who sailed it will forever remain a part of the legend and lore of the Coast Guard and the Great Lakes.