June 6, 2022 —

[Editor’s note: The following essay is adapted from a chapter of the book by Evan J. David, Our Coast Guard: High Adventures with Watchers of Our Shores (New York: D. Appleton-Century Company, 1942), 209-233.]

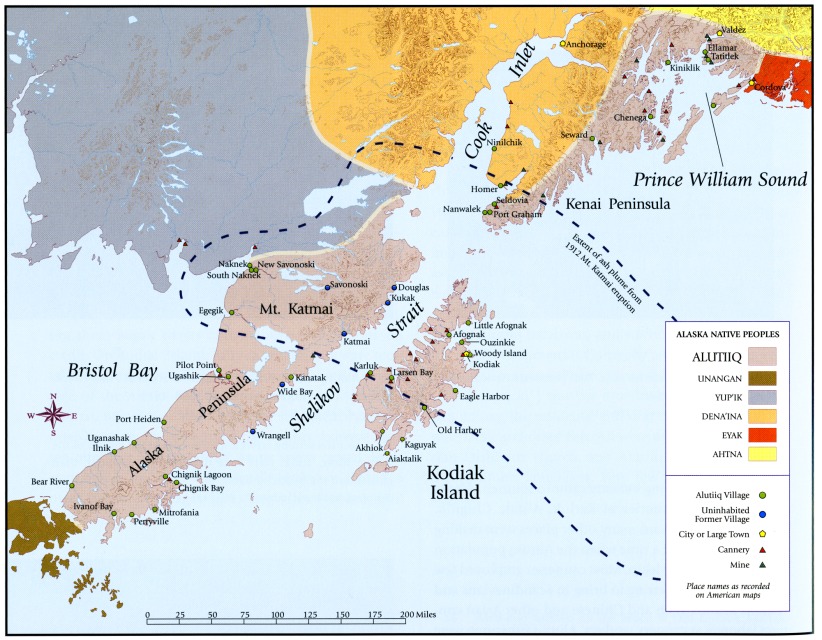

Few people know that one of the most gigantic volcanic eruptions in the history of the world, accompanied by a series of earthquakes, occurred within the confines of the United States territory as recently as 1912. Over a period of three days, a series of blasts pulverized the top of a mountain, reducing it from 7,000 to 4,000 feet in altitude, opening up a crater 12 miles long, and generating 10,000 fumaroles and geysers in a valley since named the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes.

Few people know that one of the most gigantic volcanic eruptions in the history of the world, accompanied by a series of earthquakes, occurred within the confines of the United States territory as recently as 1912. Over a period of three days, a series of blasts pulverized the top of a mountain, reducing it from 7,000 to 4,000 feet in altitude, opening up a crater 12 miles long, and generating 10,000 fumaroles and geysers in a valley since named the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes.

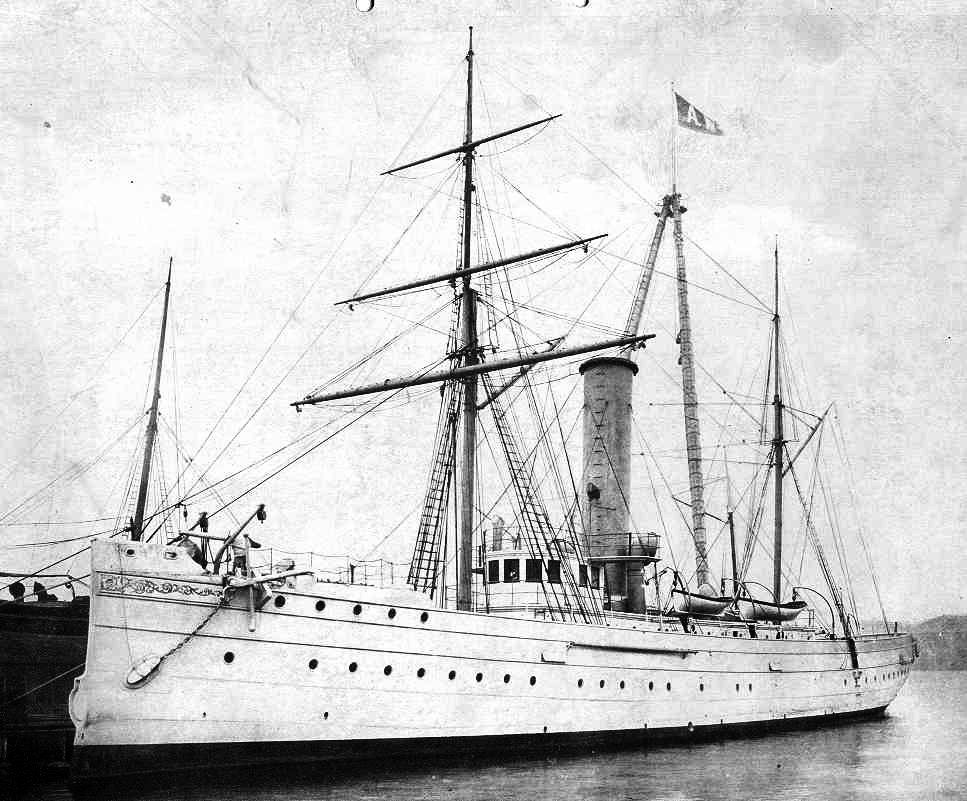

On June 6, 1912, the United States Revenue Cutter Manning lay moored outside the barge St. James, which was moored to the wharf at St. Paul, Kodiak Island, Alaska, taking on coal.

Kodiak Island is about 25 miles south of the root of the Alaskan Peninsula. The village of St. Paul was known primarily for its fishing canneries and the island as the home of the Kodiak bear, the largest in the world, some weighing nearly a ton.

At about 4:00 p.m., Capt. Kirtland Perry, on the deck of the Manning observed a peculiar cloud slowly rising to the south and southwestward. He remarked that it looked like a snowstorm, which, even in that latitude, was unusual for that time of the year. A few minutes later, thunder began to roll from that strange cloud which was now moving toward the cutter. It looked very yellowish and dense and extended very far up into the sky.

For an hour, the officers on the bridge watched the strange phenomena approach with misgivings. At 5:00 p.m., light particles of ash or pumice began to descend like white, burnt out coal cinders. They fell all around on the decks of the cutter and the barge. They were so light that they floated on the surface of the harbor like hailstones.

All the men off duty on the cutter had come on deck. The air was now filled with a sulfurous smell, which got in the nostrils and made men cough. This, together with the fine dust, began to make breathing hard. By six o’clock, the ashes fell in considerable showers, steadily increasing until  there was a continuous fall of hot cinders measuring from fine particles to ones as large as one’s fist.

there was a continuous fall of hot cinders measuring from fine particles to ones as large as one’s fist.

Meanwhile, the cloudbank had spread past the zenith, Perry and men aboard the cutter observed another cloudbank to the northward. The two met about 30 degrees above the northern and eastern horizons with a great display of thunder and lightning, which  broke through the yellow dense cloud down to the mountains on the island and the sea. The deck began to tremble. It was an earthquake shock, which lasted for a few seconds and then spent itself.

broke through the yellow dense cloud down to the mountains on the island and the sea. The deck began to tremble. It was an earthquake shock, which lasted for a few seconds and then spent itself.

The thunder and lightning continued as intense as in the tropics, and by 7:00 p.m., though it lacked two hours of sunset, black night had already settled down upon everything!

The officers and men aboard Manning tried to conjecture what had taken place to cause such a strange phenomenon. All agreed that an eruption of tremendous magnitude was taking place over on the Alaskan Peninsula, but where or how big it was no one could tell. They surmised that the thunder and lightning must be generated by continuous explosions in a gigantic crater to last so long and rain down so much pumice.

Everyone was frightened and wondered how long the ashes would fall, and how long it would take for the immense black cloud to dissipate itself, and when the thunder and lightning and earth tremors would stop! Everyone was vaguely uneasy, not only as to what might happen to them in this strange darkness, but as to how much damage might befall the ship and Kodiak Island. Fears were felt for everybody on the mainland, especially natives in the villages in the neighborhood from which this strange cloud had come.

At 9:00 p.m., four white men, their wives, and one child came down from the village through the falling ashes and darkness to the wharf and across the barge to the cutter. They had been so terrified that the women thought it was the end of the world! The captain tried to assuage their fears, welcomed them aboard and gave them somewhere to stay for the night. Shortly after, some of the inhabitants of St. Paul left their houses and stumbled down to the wharf. Perry comforted them as best he could and advised them to return to their homes. But, some of the panic-stricken women and children preferred to stay on the wharf in the hope the Manning might take them aboard if things got worse or it sailed away.

Ever since the cloud had appeared, the cutter’s radio operator had been trying to connect to some stations on the mainland, but the electrical disturbance was so great it was impossible to send anything, much less receive any information. It was also impossible to get even the powerful U.S. Navy radio station on Woody Island not far away.

Ever since the cloud had appeared, the cutter’s radio operator had been trying to connect to some stations on the mainland, but the electrical disturbance was so great it was impossible to send anything, much less receive any information. It was also impossible to get even the powerful U.S. Navy radio station on Woody Island not far away.

At regular intervals, the captain ordered specimens of the deposit to be taken and examined. It was found to consist of dust, fine sand, and granulates, clearly indicating volcanic origin. By this time it began to cover the decks. A crew of men were kept busy sweeping it off.

By midnight the thunder and lightning diminished. Occasionally it burst forth again as if the volcano went to sleep for a time and then awoke with a terrific blast. But, by this time, the natives on the wharf had returned to their homes.

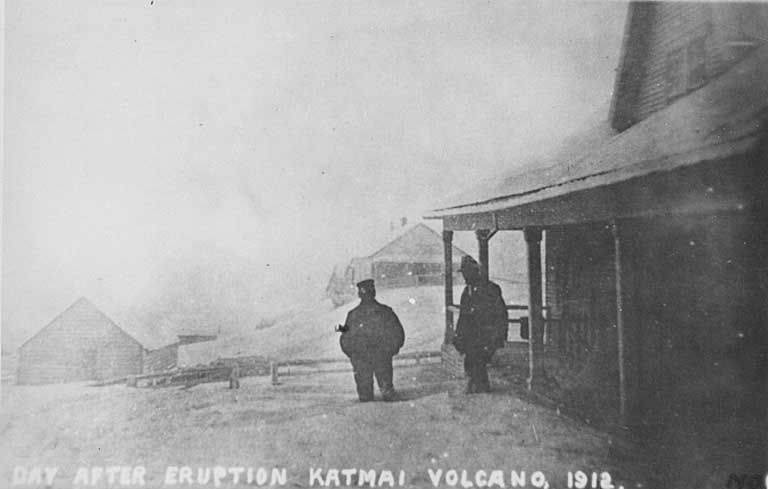

About 1:00 a.m., on June 7, volcanic matter began falling in ever-increasing density until 3:00 a.m., with all the terrors of the previous evening recurring to the people on the ship and in the town. Then it gradually diminished and ceased about 9:10 a.m., to the great rejoicing of everybody.

There was no doubt now in the minds of the officers and men that one of the many inactive volcanos on the Alaskan Peninsula had erupted with stupendous and disastrous effect. Of course, there was no way of determining exactly where the eruption had occurred and, owing to the excessive static, the cutter’s radio operators could not find out, or send out any warning to ships at sea.

Already about five inches of ashes had fallen on the decks. All the streams leading into the ocean were choked with pumice and ashes. All the wells in St. Paul were coated with this same debris. This, together with the sulfurous fumes and the dust, which got into the nostrils and throats of the inhabitants, made them very thirsty. They came down to the wharves and begged for water.

Perry ordered his men to supply the inhabitants with fresh water from the Manning. The same thing was done for the men on the schooner Metha Nelson lying at the end of the dock. This was such a drain upon the Manning that Perry had to start the evaporators to provide more drinking water. It was necessary to continue this for the next three days.

But the worst was not yet over by any means. At noon, about three hours after the ashes had stopped falling, the sky became clouded over again and ashes began to pour down, so that within a half-hour it was impossible to see 50 yards away! Again, the pyrotechnic display of lightning, the accompanying thunder, and renewed earth tremors were most terrifying.

The captain and the crew, as well as the refugees aboard the Manning, had all hoped that when the ashes ceased falling the series of eruptions were over. Now deep concern was visible on every countenance. Some of the inhabitants of St. Paul began to assemble on the dock. A few were panicky and had deserted their homes.

All now began to wonder if there ha d not been a second eruption nearby somewhere on Kodiak Island and if the Manning, the Metha Nelson, and all the inhabitants were going to be buried alive.

d not been a second eruption nearby somewhere on Kodiak Island and if the Manning, the Metha Nelson, and all the inhabitants were going to be buried alive.

The refugees suggested that it might be safer for all aboard if the Manning put out to sea. The captain put that idea up to the constantly increasing inhabitants on the wharf. Only a portion of them wished to leave, and since the opinion of the ship’s company was “take all or none,” Perry decided to stay at the wharf.

In order to see how things were in the village, Perry himself went ashore to investigate. Some of the inhabitants had taken refuge in the Russian Orthodox Church and were praying, in fear that the end of the world was at hand. Some of the rougher element had assembled in the two saloons where they were drinking heavily to drown their fears. The captain requested the proprietors to close their saloons. This they did at once, saying it was time for everyone to keep his mind clear for there was no telling what might happen to the whole island, for now there was no doubt a gigantic volcanic eruption was in operation close at hand.

By 2:00 p.m., only an hour and a half after the second fall of ash began, pitch darkness again settled over the whole island. Again, they could not tell if the crashing thunder and flashing lightning were explosions, or eruptions or an electric storm, except that the ashes fell faster and thicker than ever and the earth trembled. Whichever it was, it continued to put the radio stations out of commission.

This midday darkness was most appalling to the inhabitants and frightened them as much as the thunder and lightning and the earth tremors, which continued all through the afternoon. Again, the ashes parched all throats, clogged nostrils, and the sulfurous gases nearly strangled the people, while the pandemonium of noise, which continued into the night, prevented even the most exhausted from sleeping.

Stay tuned for part two…