May 20, 2022 —

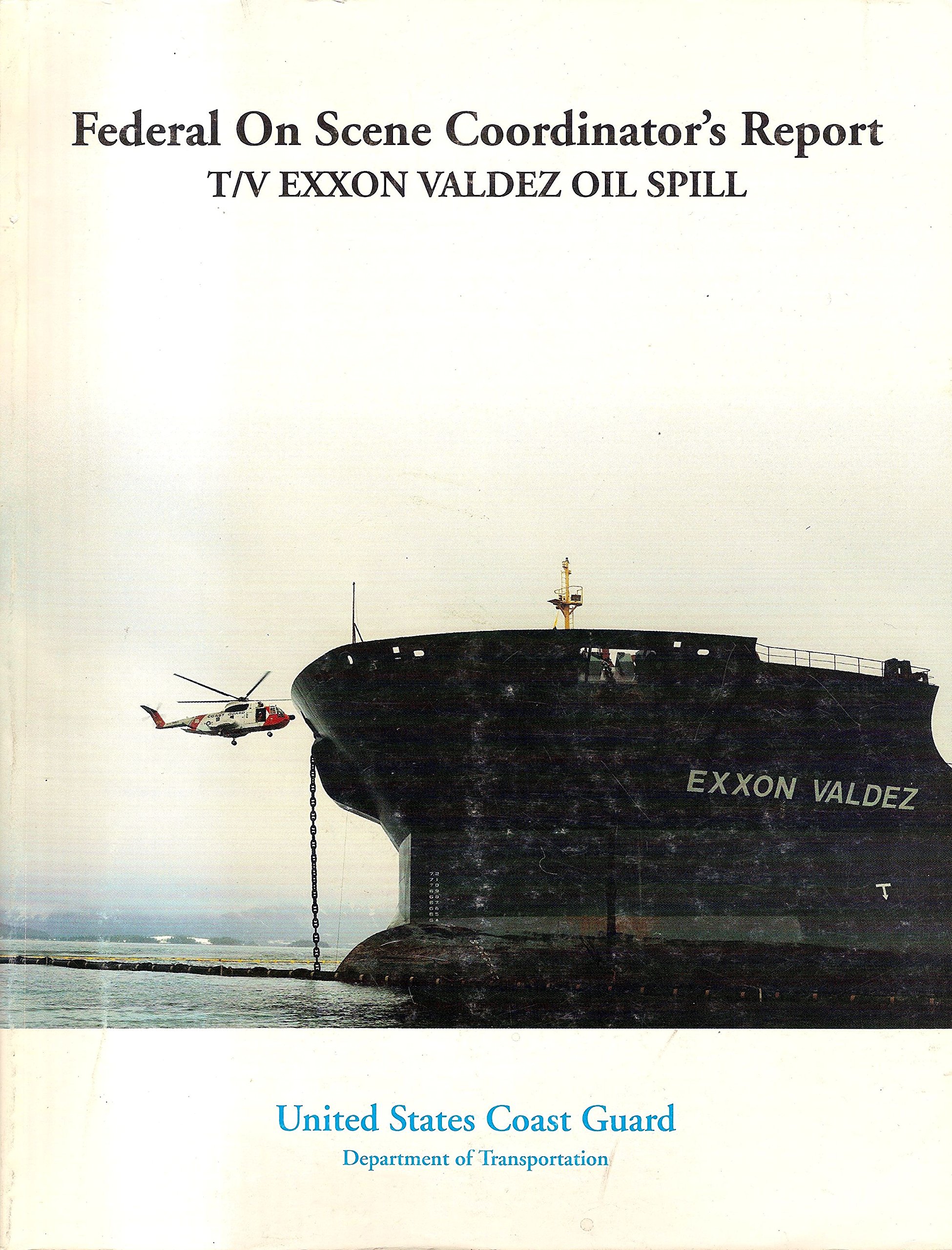

Four minutes after midnight on March 24, 1989, 11 million gallons of Alaska crude oil, also known as “Black Gold,” was instantly transformed into black death when the supertanker Exxon Valdez grounded upon Bligh Reef. It ripped a huge gash in the steel hull releasing a black death, which soon spread throughout pristine Prince William Sound killing much of its abundant marine life.

Four minutes after midnight on March 24, 1989, 11 million gallons of Alaska crude oil, also known as “Black Gold,” was instantly transformed into black death when the supertanker Exxon Valdez grounded upon Bligh Reef. It ripped a huge gash in the steel hull releasing a black death, which soon spread throughout pristine Prince William Sound killing much of its abundant marine life.

The crew at Coast Guard Station Valdez went on red alert. Four hours later, the East Coast was awakened to the horrendous news from their televisions and radios. The blame game commenced almost immediately. Grandstanding politicians hurled fiery darts and the media were demanding a scurvy dog be tied to a yardarm, or so it seemed to us at the helm of Station Valdez.

The ancient law of the sea reigns even today. The captain is always responsible for the safe navigation of the ship. It is difficult to swallow. Murphy’s Law is present in all human endeavor. “The Cause” was human error on the Exxon Valdez, and other factors were soon brought to light, including Coast Guard vessel traffic controller tested positive for THC cannabis 12 hours after the incident.

Often in the public mind, perception becomes reality. Our valiant effort after the horrendous incident at Bligh Reef could never be considered in the highest traditions of the U.S. Coast Guard. It was questioned that the Coast Guard is supposed to prevent pollution. As we stood the watch at Station Valdez following this incident, we struggled to reconcile it all.

The immediate aftermath of the event was bedlam. My dominant memory is plummeting morale and murderous lack of sleep. Our commanding officer, Capt. Steve McCall, was most graceful in crisis management. Day after day, he would arrive after precious few hours of sleep to urge us onward.

Day two, 10:00 p.m., and McCall finally leaves the station for home and sleep. Gridlock arrived and my communications center is overwhelmed. I draft a message requesting our Mobile Communications Center at Sacramento, Calif., be flown to Valdez immediately. My executive officer refuses to sign it, saying, “Wait for the captain’s return in the morning.” I am on the phone to the Coast Guard district office in Juneau informing them to expect my message in the morning. Their response: “We really can’t do anything until we get that formal message.” The lumbering bureaucracy caused me much despair. Juneau calls two hours later saying, “they are loading the plane and it will arrive in the morning.” Sweet victory!

At 7:00 a.m., I go home to sleep. At 8:30 a.m., the phone rings. I must now go set up the Mobile Communications Center. I was placed on nightly officer of the day duty, to be fully awake as the eyes and ears of Station Valdez at night, and then expected to be available during the day also.

At 7:00 a.m., I go home to sleep. At 8:30 a.m., the phone rings. I must now go set up the Mobile Communications Center. I was placed on nightly officer of the day duty, to be fully awake as the eyes and ears of Station Valdez at night, and then expected to be available during the day also.

It is 4:00 a.m. in Valdez, 8:00 a.m. in New York, and the phones light up. All news outlets wanted an update. I explained to the producer of a large cable news network that I could only read a prepared statement and he promised he would inform his “talent.” During the live interview, the reporter charged-in with a question that implied Coast Guard negligence. I ignored his question and read the approved statement provided to me with all of the professionalism I could muster under the circumstances. When I was asked a question regarding the Exxon tanker, I answered, “You will have to contact Exxon Shipping for that information.”

I thought, “Boy did I ever blow that.” I heaped condemnation upon myself because my captain and indeed the commandant of the Coast Guard is going to blast me for this. An hour later, McCall arrives looking fresh for battle. I greet him like a hangdog. However, he is beaming saying, “My father-in-law saw your interview and he said you really set them straight. Good job!” What a relief.

At home, I go for my hour ration of sleep. The phone rings, I receive order to, “go mee t with Exxon and State of Alaska communications managers to plan a radio network for spill clean-up.”

t with Exxon and State of Alaska communications managers to plan a radio network for spill clean-up.”

The Exxon representative arrived from Texas proclaiming, “We are going to build this network and Exxon will pay for it all. We don’t care how much it costs. We have to do it right away.” Wow! A blank c heck for radio. The stuff of my dreams! This really got me going despite waves of fatigue.

heck for radio. The stuff of my dreams! This really got me going despite waves of fatigue.

The State of Alaska representative informed us they also had resources nearly ready to go. They demanded the Coast Guard offer up funds as. They were looking at me, awaiting my reply, but I was dumbstruck. I had no authority and could not promise them anything. I felt totally inept in this urgent situation. I called Juneau and in a couple of days, they sent a chief warrant officer to banter with Exxon and the State of Alaska.

When McCall arrived, the Valdez station crew immediately jumped out of their seats, snapping to attention. “Station at ease” was the command. Our captain spoke of our progress and complemented our efforts. Then, leaning forward and in a very personal, sincere manner told us: “This is our battlefield, and like any military battlefield we must expect this experience will surely affect us going forward.” He was spot on! Only now, 32 years later, do I have the courage to write about the disaster at Bligh Reef on March 24, 1989—four minutes after midnight.