The all female crew of a Yerba Buena Island 41-footer; left to right: BM1 Jane Piereth, BM3 Gail Wheeler, MK1 Esther Liberman, BM1 Becky Post, BM3 Adele Fiorillo; April 1989. Photo by PA1 Ron Cabral.

[190529-G-G0000-3001]

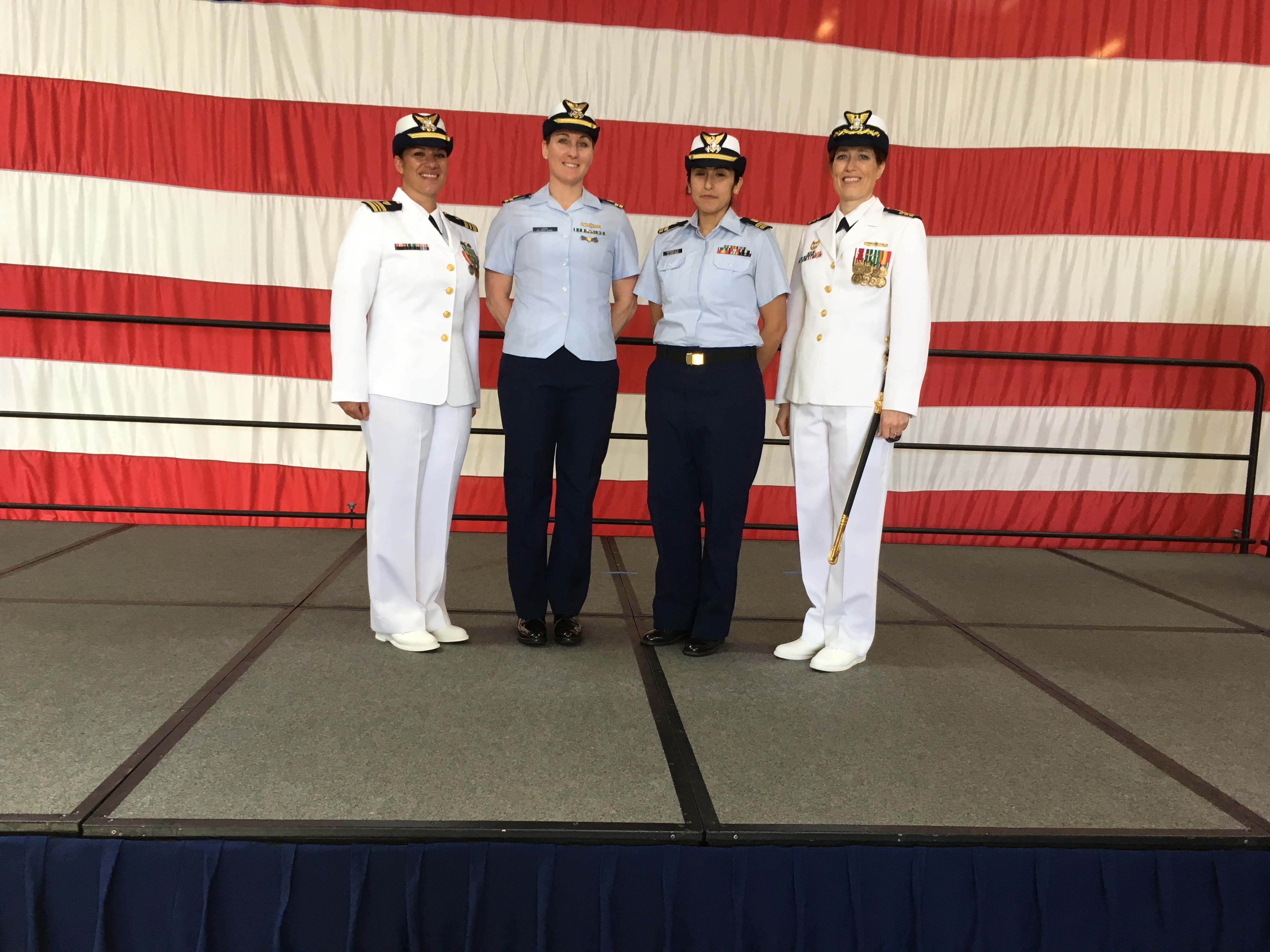

USCG Gulf Strike Team, All Female Command Cadre, Mobile, AL in 2018-2019

From left to right: LCDR Jessica Thornton, XO, LT Lucy Love, OPS, LT Samantha Marmolejo, AOPS, CDR JoAnne Hanson, CO

[191115-G-G0000-001]

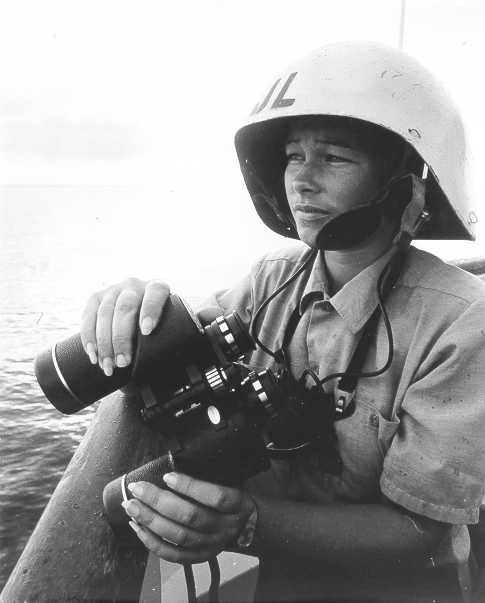

A femal Coast Guardsman on board a cutter.

[190529-G-G0000-3002]

The first African American female pilot in the Coast Guard, LTJG Jeanine McIntosh poses in front of her HC-130.

[190522-G-G0000-3009]

SPAR recruiting poster in color.

[190529-G-G0000-8001]